Engineering 100-980

Lab 3: Temperature Sensing

You should work on this assignment in pairs, but you must SUBMIT YOUR OWN INDIVIDUAL WORK. Aside from hardware photos, all submitted content must be your original work and not copied from anyone else. Submissions that are not your own may result IN POINT DEDUCTION OR A ZERO.

Contents

Materials

- 1 Arduino Nano Every

- 1 Breadboard

- 1 Programming Cable (and adapters if necessary)

- 1 TMP36 Temperature Sensor

- A handful of jumper wires

- A computer with the Arduino IDE installed and setup.

Introduction

Starting in this lab, you will be graded on your use of color coding when wiring breadboard circuits. Please take careful note of the guidelines listed below!

- Red: Power (5v, 3.3v, etc.)

- Black: Ground

- Blue: Analog (Pins labeled with an A, and most likely used for analogRead or sensor data)

- Yellow: Digital (Pins labeled with a D, most likely used to control things or for more complicated sensors)

Use of vertical breadboard rails: Utilize the breadboard rails (blue and red) to run power and ground lines for easy access across the entire breadboard. For example, run a black jumper cable from the Arduino ground pin to one of the blue rails, and then connect another black jumper from the grounded blue rail to the other blue rail. Now both blue rails are grounded and can be used as the ground terminal for any components. Similarly, you could connect a red jumper from the 5v pin on the Arduino to one of the red rails and use that rail for a 5v supply. In future labs, when we’re working with 5v and 3.3v, we will have you run a rail for each voltage.

This video goes through how to set up the TMP36 and is very useful to watch before you get started.

This lab represents the start of your journey into developing your rocket’s sensor board. Your board will measure an ensemble of variables, including temperature, pressure (to derive altitude), and acceleration. We will begin with the simplest, most visceral metric: temperature. The final sensor board on your rocket will use a digital BME680 environmental sensor for temperature measurements, but in this lab we will work with an analog TMP36 to learn about analog sensors and calibration.

A sensor is a device that provides measurement of some environmental observable. Many times, sensors work by transduction whereby they convert one form of energy into another, often times converting input to electrical energy. However, how do we know what the relationship is between the input and the output? If, for instance, the output from a temperature sensor reads as 2 Volts at room temperature, what does an output of 3 Volts mean? In order to answer this question, we need to generate a calibration curve for the sensor: an equation that maps input values against output values.

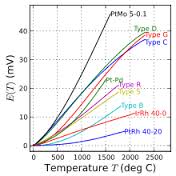

Here’s a cool example: since you’ll be dealing with a temperature sensor this lab, check out these calibration curves for different flavors of a temperature sensor that relies on a physical process called the thermoelectric effect. When two dissimilar metals are brought into contact, a voltage is generated between them that is proportional to temperature. Hence: Thermo-Electric. This sensor is called a thermocouple. In the figure below, we can see multiple calibration curves for different types of thermocouples.

Over the next few weeks, you will become very familiar with the sensors used in this course. We’ll start by looking at the TMP36 as a straightforward analog temperature sensor with built-in circuitry that produces a nearly linear calibration curve. Later, your sensor board will rely on the BME680’s digital temperature readings instead.

How Analog to Digital Converters (ADCs) Work

In lab 1, you may have figured out the form of the relationship between the raw voltage and value returned by analogRead(). However, it’s unlikely you got this relationship exactly right, as that requires a slightly deeper understanding of how they work at the physical level. We wanted you to simply begin to think about how it worked before. Now, we’ll cover this subject more deeply than both the prior labs and videos did.

To begin, we have to consider the differences between the real world and the digital world. The digital world is essentially discrete, whereas the real world is essentially continuous (we are going to ignore quantum mechanics). This means that when converting from the real world to the digital world, there will be some loss of information. This is an important fact to consider when evaluating a sensor or other tool.

The ADC we’re using in class is no exception - the maximum resolution, or how finely the instrument can be read, is controlled by the number of bits in the ADC. The more bits an ADC has, the higher the resolution. The equation below lets you calculate an approximate resolution. \(V_{ref}\) is the maximum voltage of the ADC and bits is the number of bits in the ADC.

\[Resolution = \frac{V_{ref}}{(2^{bits}-1)}\]Now, to turn the raw value returned by analogRead() into a voltage, you need to simply multiply it by the resolution of the ADC. This is shown by the formula below.

This is not exactly correct, but we will cover this in class later.

Procedure

1. Wiring the TMP36

Using the image below, take note of which pins must be connected to each circuit element.

Connecting the TMP36 backwards will quickly smell like BBQ…

Please watch the youtube video above to get the orientation right before burning your fingers.

This sensor is rather simple to interface with. When the temperature changes, the output voltage of the sensor changes as well.

2. Uploading the Code

Once your TMP36 is plugged in to your Arduino Nano Every, go to File → Examples → ENGR100-980 → Lab3-TMP36.

Note: If Lab3’s example script does not show up, your library may be out of date. To update it, first try restarting the Arduino IDE. If this doesn’t work, try following the same steps you took to install the library to update it.

You will need to modify the analog pin number you are reading off of for this lab. Unlike the last lab, where we provided a specific #define compiler variable for you to change the pin with at the top of the example script, this time, you will be changing the value yourself.

In the provided start code, locate the loop() function and find where analogRead() is called. It is set to default to pin A1, but you should change this to be whatever analog pin you plugged your TMP36 into.

Before we move on to collecting data, let’s make sure the circuit is working as expected. To do this, we want to warm up or cool down the temperature sensor. You can do this by simply putting your fingers over the sensor for a minute and watching the voltage change in your Serial Monitor. If the voltage does not change, you may have something wrong in your circuit.

3. Collecting Data

Now we have a circuit and some code to tell us the raw voltage that our TMP36 is reading, as explained above in How Analog to Digital Converters (ADCs) Work.

In order to turn this voltage into a useful temperature, we need to do some math with a calibration curve. Here is an example calibration curve spreadsheet.

To build this two-point calibration curve, we need, as the name suggests, two points. For this lab, we will collect one temperature inside, and one outside.

- Start by making a copy of the calibration curve spreadsheet you made during lecture. For those of you who did not attend lecture, see the lecture slides on Canvas, watch the lecture recording, or Google/ask a friend about how to make a calibration curve. It is quite simply a way to find the slope and offset of a linear equation to connect two points. This slope and offset are what we will use to convert our voltage into a temperature.

-

In your calibration curve copy, set aside a space to make raw measurements before entering things into the spreadsheet. This could be a simple table on a new sheet, or just a table off to the side. It should look something like this:

Voltage Temperature (°C) Indoor Test Outdoor Test - Now, let your circuit sit still on your workbench for a minute to let it adjust to the temperature in the lab. Record, using the Serial Monitor, the rough average voltage reading while it is stationary inside. Additionally, make a note of the temperature in the room, which will be written on the whiteboard in lab.

- Next, pick up your whole circuit and computer, and take a field trip outside. Find a nice spot in the sun (or out of the rain if the weather doesn’t cooperate) and again let your board sit for a while. While you wait, you should be able to watch the voltage readings in your Serial Monitor slowly level out. Once there is no longer much change between their values, take their rough average current value and record it into the table in your spreadsheet. Record this along with the current temperature outside. (You could also find a refrigerator or freezer around the building and put your board in one of these. There are thermometers in the lab that can be used to measure the temperature of an object—ask one of the IAs for one of these.)

4. Making a Calibration Curve

Now that you have filled out your basic table of indoor and outdoor (or refrigerator) temperature and voltages, plug these values into your spreadsheet to calculate your calibration curve.

Your calibration curve for a TMP36 will be linear, unlike a curve for a thermocouple as described in the introduction. This means your final calibrated equation will take the form of \(y=mx+b\), where \(m\) is the slope and \(b\) is the y-intercept.

The \(m\) and \(b\) values calculated from this step are what you will use in the next step.

5. Modifying the Code

Now we are ready to change the Arduino’s code so that instead of printing a voltage, it will print a temperature.

To do this, there are some commented out lines that define slope, intercept, and tempC. You need to now uncomment those lines (by removing the leading slashes), and update their values to whatever values you got in the previous procedure step.

Finally, we need to tell the Arduino to print out the tempC variable instead of the voltage to Serial now, so we do this by changing what variable is passed into Serial.println() from Serial.println(voltage); to Serial.println(tempC);.

Run your code again and look at the Serial Monitor. You should now see values that look like temperatures, and they should roughly match the indoor temperature. If they do, move on to the next step.

6. Field Trip Pt. 2

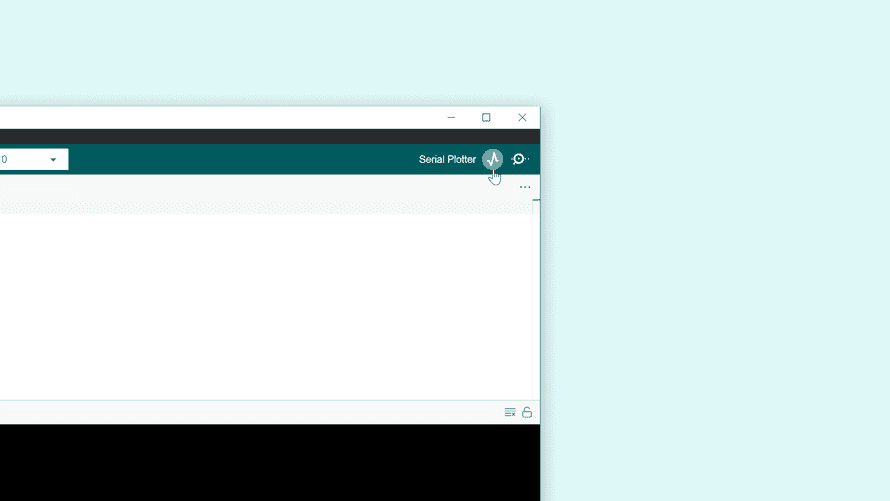

We are now finally ready to record our temperatures as we go outside. Start by opening the Serial Plotter:

You should now see temperature data being graphed in real time!

While you have the Serial Plotter open, walk outside and wait for your temperature to adjust and flatten out on your plot. Once this is done, take a screenshot of the plot. This will be one of the things you include in your submission.

Post-Lab Questions

To get you thinking critically about how your 2-point calibration curve works, as well as more comfortable with using a spreadsheet, answer the following questions:

You must show all of your work for all questions to earn full credit

- If your Arduino read in a voltage of 0.4V, what temperature would that equate to on your calibration curve?

- What would the voltage be (based on your own calibration curve) if it output a temperature of 6°C?

- What raw digital value would your Arduino be reading in for a voltage of 0V? 2.5V? 5V? If you are stuck on this, try re-reading the section about how analog to digital converters (ADCs) work and try working backwards through the Arduino code. The

analogRead()function is what actually returns the raw value, so if you know the voltage, could you re-arrange the equation given in the starter code to solve for the raw digital value?

Memo

In addition to the pdf you will create as detailed in the submission below, you will also be writing a memo for this lab.

For details about the memo, see the Canvas assignment.

Submission

Reminder: You should work on this assignment in pairs, but you must SUBMIT YOUR OWN INDIVIDUAL WORK. Aside from hardware photos, all submitted content must be your original work and not copied from anyone else. Submissions that are not your own may result IN POINT DEDUCTION OR A ZERO.

On Canvas, you will submit ONE PDF that will include all of the following:

- A screenshot of your calibration curve spreadsheet.

- Your data table of indoor and outdoor temperatures and voltages.

- A screenshot of your Arduino IDE’s Serial Plotter output showing the temperature as it changes as you walk outside.

- Answers (and any work you may have) to the post-lab questions.

- Photo of completed breadboard circuit.

(COLOR CODING WILL BE GRADED)

To put said content into a PDF, it is suggested you create a new Google Doc and paste your images and write your text in the document. Export/Download this document as a PDF and upload it. DO NOT SUBMIT A GOOGLE DOC FILE OR SPREADSHEET FILES.

Submitting anything other than a single PDF may result in your work not being graded or your scores being heavily delayed.

Separately:

- Also upload your memo as a PDF to the Memo 1 - Temperature Sensing assignment on Canvas. This memo is a completely separate submission from the PDF you turn in for this lab.